President Who? Forgotten Founders - Chapter 4 - By Stanley L. Klos

John Hancock

Seventh

President of the United States

in Congress Assembled

November 23,

1785 to June 5, 1786

3rd President of the Continental Congress

of the United Colonies of America

1st President of the Continental Congress

of the United States of America

About The Forgotten Presidents'

Medallions

© Stan Klos has a worldwide copyright on the artwork in this Medallion.

The artwork is not to be copied by anyone by any means

without first receiving permission from Stan

Klos.

U S Mint

and Coin Act

- --

Click Here

The First

United American Republic

Continental Congress of the United Colonies

Presidents

Sept. 5, 1774 to July 1, 1776

Commander-in-Chief United

Colonies of America

George Washington:

June 15, 1775 - July 1, 1776

The Second

United American Republic

Continental

Congress of the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

Commander-in-Chief United

Colonies of America

George Washington:

July 2, 1776 - February 28, 1781

The Third

United American Republic

Presidents of the United States in Congress Assembled

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

|

Samuel Huntington |

March 1, 1781 |

July 6, 1781 |

|

Samuel Johnston |

July 10, 1781 |

Declined Office |

|

Thomas McKean |

July 10, 1781 |

November 4, 1781 |

|

John Hanson |

November 5, 1781 |

November 3, 1782 |

|

Elias Boudinot |

November 4, 1782 |

November 2, 1783 |

|

Thomas Mifflin |

November 3, 1783 |

June 3, 1784 |

|

Richard Henry Lee |

November 30, 1784 |

November 22, 1785 |

|

John Hancock |

November 23, 1785 |

June 5, 1786 |

|

Nathaniel Gorham |

June 6, 1786 |

February 1, 1787 |

|

Arthur St. Clair |

February 2, 1787 |

January 21, 1788 |

|

Cyrus Griffin |

January 22, 1788 |

January 21, 1789 |

Commander-in-Chief United

Colonies of America

George Washington:

March 1, 1781 - December 23, 1783

John Hancock was born in Quincy, Massachusetts,

on January 12, 1737 and died there October 8, 1793. Hancock received a

privileged childhood education and was admitted to Harvard graduating in 1754.

Upon the death of his father, John Hancock was adopted by his uncle, Thomas, who

employed him at the Hancock counting-house. Upon his Uncle’s death John Hancock

inherited the thriving business as well as a sizable fortune which some scholars

claim was amassed during the French and Indian War.

On November 1, 1765, in an effort to recoup loss

revenues due to the war, the British Parliament, imposed a direct tax on the

American Colonies. This tax was to be paid directly to King George III to

replenish the royal treasuries coffers emptied by his father during the height

of the 7 Years War. Under the British Stamp Act, all printed materials including

broadsides, newspapers, pamphlets, bills, legal documents, licenses, almanacs,

dice and playing cards, were required to carry a revenue stamp. Americans who

for 160 years faithfully paid taxes to their respective colonial governments

were, for the first time, expected to pay this additional tax directly to Great

Britain.

The colonists, in opposition to King and

Parliament, convened the Stamp Act Congress in New York City on October 19,

1765. They passed a resolution which made “the following declarations of

our humble opinion, respecting the most essential rights and liberties Of the

colonists, and of the grievances under which they labour, by reason of several

late Acts of Parliament” calling on King George III to repeal the Act.. The

Act was repealed on March 18, 1766 but it was replaced with the Declaratory

Act. This Act asserted that the British government had absolute authority over

the American colonies which further divided the two political systems.

In that same

year Hancock was chosen to represent Boston in the Massachusetts House of

Representatives with James Otis, Thomas Cushing, and Samuel Adams. In the

House, Eliot says of Hancock, that "he blazed a Whig of the first magnitude"

defying the taxes of the British Empire. The seizure of Hancock’s sloop, the

"Liberty," for an alleged evasion of the laws of trade, caused a riot in

Massachusetts, with the royal commissioners of customs barely escaping with

their lives.

In 1767, in

another attempt to obtain revenue from the colonies, the Townshend Revenue Acts

were passed by Parliament, taxing imported paper, tea, glass, lead and paints.

In February of 1768, Samuel Adams and James Otis drafted and the Massachusetts

Assembly adopted a circular letter to be sent to the other American Assemblies

protesting these taxes. They expressed the hope that redress could be obtained

through petitions to King George III. The letter called for a convention to

thrash out the issue of taxation without

representation and issue a unified address to the Crown. The British government,

however, provoked a confrontation by ordering the Massachusetts Assembly to

rescind the letter and ordered Governor Bernard to dismiss the assembly if they

refused.

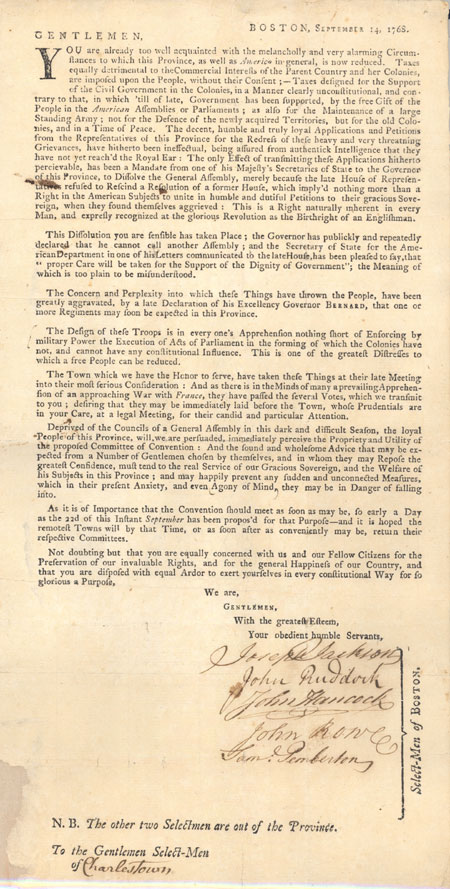

In protest to

this and other British laws, John Hancock and other Selectman called for a

statewide “town meeting” at Faneuil Hall on September 23, 1768.. 96

towns answered Hancock’s call to address taxation and self-government grievances

against the British Crown n September 28th. The circular produced by Hancock

calling for the meeting read:

Image Courtesy of Seth Kaller

“YOU are already too well acquainted with the _hreatenin [sic] and very

alarming Circumstances to which this Province, as well as America in general, is

now reduced. Taxes equally detrimental to the Commercial interests of the Parent

Country and her Colonies, are imposed upon the People, without their Consent; -

Taxes designed for the Support of the Civil Government in the Colonies, in a

Manner clearly unconstitutional, and contrary to that, in which ‘till of late,

Government has been supported, by the free Gift of the People in the American

Assemblies or Parliaments; as also for the Maintenance of a large Standing Army;

not for the Defence [sic] of the newly acquired Territories, but for the old

Colonies, and in a Time of Peace. The decent, humble and truly loyal

Applications and Petitions from the Representatives of this Province for the

Redress of these heavy and very _hreatening [sic] Grievances, have hitherto been

ineffectual…The only Effect…has been a Mandate…to Dissolve the General Assembly,

merely because the late House of Representatives refused to Rescind a Resolution

of a former House, which imply’d nothing more than a Right in the American

Subjects to unite in humble and dutiful Petitions to their gracious Sovereign,

when they found themselves aggrieved…

“The Concern and Perplexity into which these Things have thrown the People,

have been greatly aggravated, by a late Declaration of his Excellency Governor

BERNARD, that one or more Regiments may soon be expected in this Province…

“Deprived of the Councils of a General Assembly in this dark and difficult

Season, the loyal People of this Province, will, we are persuaded, immediately

perceive the Propriety and Utility of the proposed Committee of Convention…”.

Forgotten U.S.

Capitols 1774-1789

18x24 Poster

Signed “John

Hancock,” also signed “Joseph Jackson,” “John Ruddock,” “John Rowe,” and

“Samuel Pemberton” as Selectmen of Boston.”

This particular Hancock document had

a demonstrable effect, “it changed the world,” as the governor called for

British reinforcements. Hancock’s convention composed a list of grievances,

passed several resolutions, and adjourned. Two days later, royal transports

unloaded British troops at the Long Wharf and began a military occupation of

Boston that would last until March 17, 1776. It was the beginning of the end of

British Colonialism in America.

In response to

the affray known as the "Boston Massacre," on March 5th, 1770 Hancock, at

the funeral of the slain Bostonians, delivered an address to the mourning

citizens. So radiant and fearless was the speech in its condemnation of the

conduct of the soldiery and their leaders that it greatly offended the Colonial

Governor. Hancock's speech was printed in key American newspapers broadening

his notoriety throughout the colonies.

In 1774 Hancock

was elected, with Samuel Adams, to the Provincial congress at Concord,

Massachusetts, and he subsequently became its president. The commanding General

ordered a military expedition to Concord in April, 1775 to capture these Hancock

and Adams. This military movement resulted in the Battle of Lexington. The

British's arrival on April 18, 1775 forced Joseph Warren to call out the

"Minute Men". Upon learning of the British plans to capture Hancock and

Adams, Warren dispatched Paul Revere who wrote "About 10 o'clock, Dr. Warren

Sent in a great haste for me, and begged that I would immediately Set off for

Lexington, where Messrs. Hancock and Adams were..."

Revere was

rowed across the Charles River to Charlestown by two friends where he checked

first with members of the Sons of Liberty that Warren's call to arms Old Church

signals had been seen. Revere then borrowed a horse from Deacon Larkin and began

his famous ride. Revere reported on his ride north along the Mystic River, "I

awakened the Captain of the minute men; and after that I alarmed almost every

house till I got to Lexington. I found Messrs. Hancock and Adams at the Rev. Mr.

Clark's; I told them my errand ..." . Revere then helped Adams and Hancock

escape, and at 4:30am he wrote that "Mr Lowell asked me to go to the Tavern

with him, to git a Trunk of papers belonging to Mr. Hancock. We went up Chamber;

and while we were giting the Trunk, we saw the British very near, upon a full

March." It was at that time, while collecting the trunk that Revere recalls

hearing "The shot heard 'round the world" on the Lexington Green. Revere

wrote,

"When we got about 100 Yards from the meeting-House the British Troops

appeared on both Sides... I saw and heard a Gun fired... Then I could

distinguish two Guns, and then a Continual roar of Musquetry; Then we made off

with the Trunk.".

Hancock and

Adams both escaped with their lives.

Following the

April battles at Lexington and Concord, the British soldiers returned to Boston

quartering the community. On 12 June, General Gage issued a proclamation

offering pardons to all the rebels, excepting Samuel Adams and John Hancock,

"whose offences," it was declared, "are of too flagitious a nature to admit of

any other consideration than that of condign punishment."

On June 16th

Colonel William Prescott was ordered onto the Charlestown Peninsula to occupy

Bunker Hill to defy the British occupation of Boston. For reasons that are still

not entirely clear, the colonists took possession of neighboring Breed's Hill

and constructed defense fortifications. General William Howe quickly assembled a

force of 3,000 soldiers to the foot of the American position. Two uphill

assaults were launched and repulsed by Colonel Prescott who reputedly cautioned

his men "not to fire until they saw the whites of their eyes." The

assaults resulted in heavy losses for the British forcing Howe to call for 400

additional soldiers.

The British

third charge caught the Americans low on powder and unable to resist the

overwhelming numbers of fixed British bayonets. Prescott ordered the retreat

down the north slope of Breed's Hill. Many were shot in the back during this

escape across the Neck. A key causality was Dr. Joseph Warren, who was among the

last to leave his position. He was killed instantly by a musket ball in the

back of his head. His death provided a political vacuum that John Hancock would

fill leading to a U.S. founding prominence second only to George Washington.

Mr. Hancock was

a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress from 1775 until 1780,

and from 1785 until 1786, serving as President of that body from May 25, 1775

until October 1777. The 2nd Continental Congress opened on May 10, 1775 with

Peyton Randolph serving as President. As in 1774 Randolph was called to Virginia

for a Burgesses session and forced to abandon his presiding chair. Henry

Middleton declined to serve as President a second time due to ill health. Samuel

Adams and his cousin John Adams champion the cause of their wealthy benefactor

John Hancock who was elected President on May 25th, 1775. The Adam’s regretted

their decision because Hancock aligned himself with delegates who were, at best,

tepid in the cause of independence. Additionally Hancock used his office in an

opulent fashion much to the disappointment of his Massachusetts Colleagues.

Moreover, when Randolph returned to Congress Hancock made no overture to

surrender the Presidency, despite many delegates charging his election was only

to serve during Randolph’s absence.

The Hancock

presidency was most eventual starting with a July 6, 1775 resolution,

"Declaration of the Causes and Necessities of Taking Up Arms," that rejected

independence but asserted that Americans were ready to die rather than be

enslaved. In this resolution Congress openly invoked their Christian God

stating:

“Our cause is just. Our union is perfect. Our internal resources are great,

and, if necessary, foreign assistance is undoubtedly attainable. -- We

gratefully acknowledge, as signal instances of the Divine favour towards us,

that his Providence would not permit us to be called into this severe

controversy, until we were grown up to our present strength, had been previously

exercised in warlike operation, and possessed of the means of defending

ourselves. With hearts fortified with these animating reflections, we most

solemnly, before God and the world, declare, that, exerting the utmost energy

of those powers, which our beneficent Creator hath graciously bestowed upon us,

the arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume, we will, in defiance

of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverence, employ for the

preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die freemen

rather than to live slaves.”

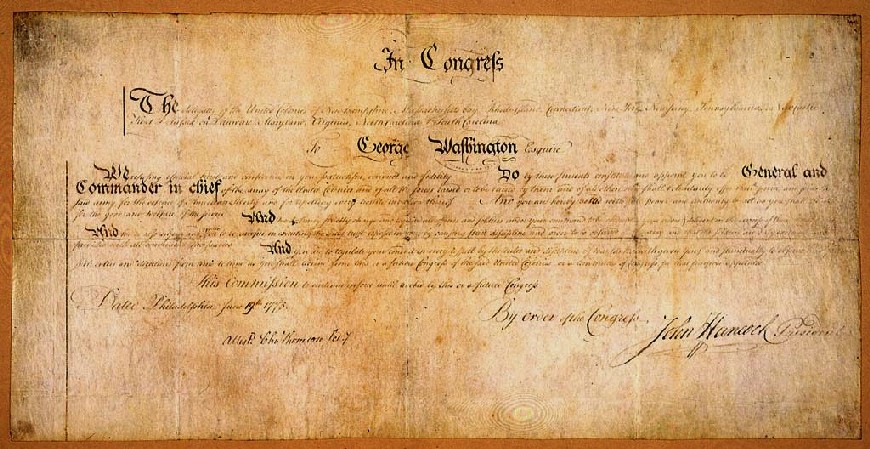

On June 14,

debate opens in Congress on the appointment of a commander-in-chief of

Continental forces. John Hancock made it known to all the delegates that he

wanted the high office and as President expects to be nominated. He is

surprised when his fellow Massachusetts delegate, John Adams, moves to appoint

George Washington suggesting he had the military experience necessary to wage

war and character around which all the colonies might unite.On June 17th, 1775

the Continental Congress passed the following resolution appointing George

Washington as Commander-In-Chief:

Resolved unanimously upon the question, Whereas, the delegates of all

the colonies, from Nova-Scotia to Georgia, in Congress assembled, have

unanimously chosen George Washington, Esq. to be General and commander in

chief, of such forces as are, or shall be, raised for the maintenance and

preservation of American liberty; this Congress doth now declare, that they

will maintain and assist him, and adhere to him, the said George Washington,

Esqr., with their lives and fortunes in the same cause.

John Adams

wrote his wife this concerning the appointment:

I can now

inform you that the Congress have made Choice of the modest and virtuous, the

amiable, generous and brave George Washington Esqr., to be the General of the

American Army, and that he is to repair as soon as possible to the Camp before

Boston.

George Washington's Commission signed

by President John Hancock - Image Courtesy of

George

Washington Papers at the Library of Congress

On July 26,

1775 John Hancock's Continental Congress established the Colonial Post office

with this resolution:

“That a postmaster General be appointed for the United Colonies, who shall

hold his office at Philadelphia, and shall be allowed a salary of 1000 dollars

per annum for himself, and 340 dollars per annum for a secretary and

Comptroller, with power to appoint such, and so many deputies as to him may seem

proper and necessary.

That a line of posts be appointed under the direction of the Postmaster

general, from Falmouth in New England to Savannah in Georgia, with as many cross

posts as he shall think fit.

That the allowance to the deputies in lieu of salary and all contingent

expenses, shall be 20% on the sums they collect and pay into the General post

office annually, when the whole is under or not exceeding 1000 Dollars, and 10%

for all sums above 1000 dollars a year.

That the rates of postage shall be 20% less than those appointed by act of

Parliament1. That the several deputies account quarterly with the general post

office, and the postmaster general annually with the continental treasurers,

when he shall pay into the receipt of the Sd Treasurers, the profits of the Post

Office; and if the necessary expense of this establishment should exceed the

produce of it, the deficiency shall be made good by the United Colonies, and

paid to the postmaster general by the continental Treasure.

The Congress then proceeded to the election of a postmaster general for one

year, and until another is appointed by a future Congress, when Benjamin

Franklin, Esquire was unanimously chosen.”

In November of

1775 Congress established both the Continental Marines and Navy on the news of

Continental Army’s Victory in Montreal. December of 1775 brought the disastrous

news that Generals Richard Montgomery and Arnold's attack on the key to Canada,

Quebec City failed. General Montgomery was killed and Benedict Arnold was forced

to make a hasty retreat into New York. This loss put a great strain on troops

and resources while shifting the main thrust of the war back to the Colonies.

On January

16th, 1776 the Continental Congress approved the enlistment of "free negroes."

This led to the establishment of the First Rhode Island Regiment, composed

of 33 free-negroes and 92 slaves. The regiment distinguished itself at the

Battle of Newport and the slaves were freed at the end of the war. Also in

January Thomas Paine publishes "Common Sense", which was a contemptuous

attack on King George III's reign over the colonies. Paine's work united many

Americans in the Revolutionary Cause by successfully arguing that the Colonists

now had a moral obligation to reject monarchy.

Paine's first

edition sold out quickly and within three months, it is estimated that over

120,000 copies had been printed. Signer Benjamin Rush recalled that

"Its effects were sudden and extensive upon the American mind.. It was read

by public men, repeated in clubs, spouted in Schools, and in one instance,

delivered from the pulpit instead of a sermon by a clergyman in Connecticut.."

The work

so inspired George Washington that he swept away all remaining allegiance to

King George III declaring that Common Sense offered "...sound doctrine

and unanswerable reasoning." for independence.

Paine's

provocative pamphlet was translated into French and appeared first in Quebec.

John Adams wrote that "Common Sense was received in France and in all Europe

with Rapture.” Common Sense was translated into German, Danish, and Russia.

It was estimated that over 500,000 copies were sold during the initial years of

the Revolutionary War.

John Hancock's

Congress capitalized on this ground swell of Paine Patriotism by invocating the

aid of God in this moral cause for independence. This time the name of Jesus

Christ was actually included in the official congressional resolution passed on

March 16th, 1776. This proclamation signed by President Hancock set May 17,

1776:

"Day of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer" throughout the colonies. The

Continental Congress urged its fellow citizens to "confess and bewail our

manifold sins and transgressions, and by a sincere repentance and amendment of

life, appease his [God's] righteous displeasure, and through the merits and

mediation of Jesus Christ, obtain his pardon and forgiveness."

The

Colony of Massachusetts followed suit almost immediately ordering a "suitable

number" of these proclamations to be printed so "that each of the

religious Assemblies in this Colony, may be furnished with a Copy of the same"

and added the motto "God Save This People" as a substitute for

"God Save the King."

Common Sense

changed the political climate in America as the pamphlet ignited debates

where the people spoke openly and often for independence. The Second Continental

Congress would take to heart Paine's suggestion::

“To conclude:

However strange it may appear to some, or however unwilling they may be to think

so, matters not, but many strong and striking reasons may be given, to show,

that nothing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined

declaration for independence.”

Common Sense

was expertly peppered with evocations to Almighty God and biblical quotes that

theologically makes a case for Independence from Great Britain. Clearly, the Day

of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer resolution passed by Congress in the Spring

of 1776 draws strongly from the popular Judeo-Christian verbiage in Paine's best

selling pamphlet..

Specifically

the 1776 Journals of Congress record the resolution as:

Mr. W[illiam] Livingston, pursuant to leave granted, brought in a resolution

for appointing a fast, which & par being taken into consideration, ∥ was

agreed to as follows:

In times of impending calamity and distress; when the liberties of America

are imminently endangered by the secret machinations and open assaults of an

insidious and vindictive administration, it becomes the indispensable duty of

these hitherto free and happy colonies, with true penitence of heart, and the

most reverent devotion, publickly to acknowledge the over ruling providence of

God; to confess and deplore our offences against him; and to supplicate his

interposition for averting the threatened danger, and prospering our strenuous

efforts in the cause of freedom, virtue, and posterity.

The

Congress, therefore, considering the warlike preparations of the British

Ministry to subvert our invaluable rights and priviledges, and to reduce us by

fire and sword, by the savages of the wilderness, and our own domestics, to the

most abject and ignominious bondage: Desirous, at the same time, to have people

of all ranks and degrees duly impressed with a solemn sense of God's super

intending providence, and of their duty, devoutly to rely, in all their lawful

enterprizes, on his aid and direction, Do earnestly recommend, that Friday, the

Seventeenth day of May next, be observed by the said colonies as a day of

humiliation, fasting, and prayer; that we may, with united hearts, confess and

bewail our manifold sins and transgressions, and, by a sincere repentance and

amendment of life, appease his righteous displeasure, and, through the merits

and mediation of Jesus Christ, obtain his pardon and forgiveness; humbly

imploring his assistance to frustrate the cruel purposes of our unnatural

enemies; and by inclining their hearts to justice and benevolence, prevent the

further effusion of kindred blood. But if, continuing deaf to the voice of

reason and humanity, and inflexibly bent, on desolation and war, they constrain

us to repel their hostile invasions by open resistance, that it may please the

Lord of Hosts, the God of Armies, to animate our officers and soldiers with

invincible fortitude, to guard and protect them in the day of battle, and to

crown the continental arms, by sea and land, with victory and success:

Earnestly beseeching him to bless our civil rulers, and the representatives of

the people, in their several assemblies and conventions; to preserve and

strengthen their union, to inspire them with an ardent, disinterested love of

their country; to give wisdom and stability to their counsels; and direct them

to the most efficacious measures for establishing the rights of America on the

most honourable and permanent basis--That he would be graciously pleased to

bless all his people in these colonies with health and plenty, and grant that a

spirit of incorruptible patriotism, and of pure undefiled religion, may

universally prevail; and this continent be speedily restored to the blessings of

peace and liberty, and enabled to transmit them inviolate to the latest

posterity. And it is recommended to Christians of all denominations, to assemble

for public worship, and abstain from servile labour on the said day.

Resolved, That

the foregoing resolve be published.

John Hanock, President

Charles Thomson, Secretary

This proclamation was printed in

full in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 20 March, 1776. There were many more 1776

events in Hancock's Congress that are noteworthy in the march towards

Independence but all are reduced to historical footnotes due to Richard Henry

Lee's June resolution and Thomas Jefferson's pen of independence. Despite his

attempts to thwart revolution, John Hancock was caught up in the "Common

Sense" fervor and ended-up presiding over the Continental Congress who would

vote to abolish all ties with Great Britain.

More on John Hancock

Click Here

Click Here

In this powerful, historic work, Stan Klos unfolds the complex 15-year

U.S. Founding period revealing, for the first time, four distinctly

different United American Republics. This is history on a splendid scale --

a book about the not quite unified American Colonies and States that would

eventually form a fourth republic, with

only 11 states, the United States of America: We The People.