Thomas Mifflin 5th President of the United States of America - President

Who? Forgotten Founders - By: Stanley L. Klos

Thomas Mifflin

5th President of the

United States

in Congress Assembled

November 3, 1783 to

November 2, 1784

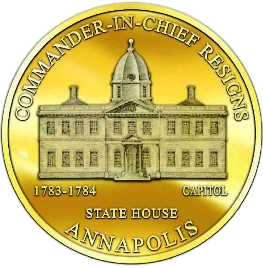

About The Forgotten Presidents' Medallions

© Stan Klos has a worldwide copyright on the artwork in this Medallion.

The artwork is not to be copied by anyone by any means

without first receiving permission from Stan

Klos.

U S Mint and Coin Act - --

Click Here

The

First United American Republic

Continental Congress of the United Colonies Presidents

Sept. 5, 1774 to July 1, 1776

Commander-in-Chief

United Colonies of America

George Washington: June 15, 1775 - July 1,

1776

The

Second United American Republic

Continental Congress of

the United States Presidents

July 2, 1776 to February 28, 1781

Commander-in-Chief United Colonies of America

George Washington: July 2, 1776 - February

28, 1781

The

Third United American Republic

Presidents of the United States in Congress Assembled

March 1, 1781 to March 3, 1789

|

Samuel Huntington |

March

1, 1781 |

July

6, 1781 |

|

Samuel Johnston |

July

10, 1781 |

Declined Office |

|

Thomas McKean |

July

10, 1781 |

November 4, 1781 |

|

John Hanson |

November 5, 1781 |

November 3, 1782 |

|

Elias Boudinot |

November 4, 1782 |

November 2, 1783 |

|

Thomas Mifflin |

November 3, 1783 |

June

3, 1784 |

|

Richard Henry Lee |

November 30, 1784 |

November 22, 1785 |

|

John Hancock |

November 23, 1785 |

June

5, 1786 |

|

Nathaniel Gorham |

June

6, 1786 |

February 1, 1787 |

|

Arthur St. Clair |

February 2, 1787 |

January 21, 1788 |

|

Cyrus Griffin |

January 22, 1788 |

January 21, 1789 |

Commander-in-Chief

United Colonies of America

George Washington: March

1, 1781 - December 23, 1783

Thomas Mifflin was

born in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 10, 1744

into a fourth generation of his family and grew-up in the city of "Brotherly

Love". His father was a Quaker, served as a Philadelphia

alderman and was also a trustee of the College of Philadelphia which is today

the University of Pennsylvania. Mifflin attended Philadelphia's grammar schools

and graduated in 1760 from the College. Upon graduation, he apprenticed at an

important counting house in Philadelphia.

In the course of this business Mifflin traveled throughout Europe

in 1764 and 1765. In 1766 he returned to the colonies early and opened an import

and export business with a younger brother. In 1767 he joined the American

Philosophical Society, served as it Secretary for two years and remained

a distinguished member until 1799.

Mifflin's entrepreneurial pursuits were responsible for the formulation of his

initial objections and protests of Parliament's taxation policy. In his

first year as a Philadelphia Importer he found it necessary to publicly speak

and campaign against Great Britain's initial attempts to levy taxes on the

colonies. In 1771 Mifflin ran and won election as a Philadelphia's warden. The

following year he began the first of

four uninterrupted terms in the Colonial State Legislature of Pennsylvania. In 1773 Merchant Mifflin met Merchant John

Hancock and political activist Samuel Adams to

learn about the British injustices levied against the people of Boston.

Adams and Hancock convinced him to join their cause of open resistance to

Parliament as it was a businessman's only judicious option to resist taxes

“imposed upon the people against their will.” In that same year Mifflin

began to organized several Pennsylvania town meetings to support Boston's

resistance to the Coercive Acts. In these meetings Mifflin cautioned that

although the acts only applied to Boston in reprisal to the "Tea Party";

successful implementation would embolden Parliament to punish other cities that

objected to seemingly perpetual wave of superfluous British taxation.

His no taxation without

representation stance and efforts in state government were rewarded in 1774 by

being elected as a Pennsylvania Delegate to the 1st Continental Congress. His

business and patriotic fervor was embraced by his fellow Delegates as the

leadership appointed him to serve on important committees. One Mifflin committee

founded a Continental Association to enforce the resolution passed by Congress

which, created an embargo against English goods. His diligence as a delegate

insured his re-election to the 2nd Continental Congress. When the news came of

the fight at Lexington Mifflin eloquently advocated resolute action in the

Continental Congress and then attended many Pennsylvania town-meetings

supporting colonial armed resistance. His direct involvement in recruiting armed

patriots was most potent as Mifflin and John Dickinson were instrumental in

reviving the volunteer colonial defense force that resisted the French in the

1750's and 60's known as the Associators. Once these troops were

enlisted, Mifflin was elected a Major becoming active in organizing and drilling

the 3rd Philadelphia Battalion. He service forced him to severe his religious

ties with Quaker Society as he prepared for war. This was an action that spoke

volumes to his commitment to Colonial self-government and defense as he was one

of the few legislators ready to substitute Continental Congress ballots with

bullets.

When the 2nd Continental Congress created the Colonial Army as a national armed

force on June14th, 1775, Mifflin held to his convictions resigning as delegate

and enlisting as a Pennsylvania Militia Major to serve with the new

Commander-in-Chief, George Washington.

General Washington, who knew Mifflin as a fellow delegate, promoted him as his

first aide-de-camp after the establishment of the command headquarters at

Cambridge. While there, Colonel Mifflin successfully led a force against a

British detachment placing the heavy artillery stripped from Fort Ticonderoga on

Dorchester Heights. This was a strategic move that ended Britain's occupation in

Boston. Mifflin also managed the complex logistics of moving troops to meet a

British thrust at New York City. In July 1775, he was promoted to

quartermaster-general of the army; after the evacuation of Boston by the enemy.

Mifflin was commissioned as brigadier-general on May 19th, 1776 and assigned to

the command of a Pennsylvania troops when the army lay encamped before New York.

General Mifflin's Pennsylvania brigade was described as the best disciplined of

any in the Continental Army. His Regiment covered the retreat of the American

army from Brooklyn after General William Howe, in

the dead of night outmaneuvered Washington. At dawn the continental troops were

forced to fight British regulars in a superior position and fell back to the

East River. Washington's only hope was to assemble enough boats to quietly cross

the river into Manhattan and as luck would have it the night brought a thick fog

over the entire area. Through a military order gaffe General Mifflin received

the word to retreat before all of the troops had embarked to Manhattan Island.

At the ferry, upon learning of the error, Mifflin managed to regain the lines

before the enemy discovered that the post was deserted and uncovered the daring

water retreat across the East River. Mifflin's troops remained at their posts

and were the last to leave Brooklyn in the hasty nighttime evacuation.

Washington's rapid retreat across the East River meant that wagons containing

most of the Continental Army's powder, baggage and critical supplies fell into

to the hands of the British. In the aftermath soldier moral was low and the

Continental Congress held a committee hearing. After a three-day investigation

the committee recommended that quartermaster Moylan, who was given the

impossible task to protect the British controlled waterways resign. In an effort

to restore the morale of the soldiers, against his wishes, Mifflin was appointed

this position by a special resolve of Congress. This new assignment as

Quarter-Master-General bitterly disappointed Mifflin who was also unhappy

with General Nathanael Greene emerging as

Washington's principal military adviser, a role which Mifflin coveted. George

Washington did not object to Mifflin's re-assignment and the disgruntled

quarter-master assumed the mundane duties of protecting and delivering the

supply necessary for the Continental Army.

The Journal of Congress reported:

Resolved, That Brigadier

General Mifflin be authorized and requested to resume the said office, and that his rank and

pay, as brigadier, be still continued to him:1[Note 1: 1 "We have obtained

Colonel Moylan's resignation, and General Mifflin comes again into the office

of Quartermaster General." Elbridge Gerry to Horatio Gates, 27 September

1776.]

That a committee of three four be appointed to confer with Brigadier General

Mifflin: The members chosen, Mr. Richard Henry Lee, Mr. Roger Sherman, Mr.

John Adams, and Mr. Elbridge Gerry.”

In November 1776, General Mifflin was

sent to Philadelphia to report to the Continental Congress the critical

condition of the army. Washington was unable to hold onto Manhattan Island and

witnessed the loss of Fort Washington, that was garrisoned with a large

contingent of soldiers, ammunition, weapons and supplies, helplessly from the

New Jersey Palisades. The Continental Army was outgunned and manned and unable

to make a stand in New Jersey to stop the advancing British march towards

Philadelphia. Additionally, Washington was out of supplies and money to pay the

troops whose tours of duty were set to expire in 60 days in the early winter of

1776. It was a wise move by the Commander-in-Chief to send General Mifflin to

rally Philadelphia, as Congress in fear of losing the Capital, was preparing to

take flight to Baltimore. Washington's Continental Army was forced to cross the

Delaware into Pennsylvania and it was then that the citizens of Philadelphia

began to panic. Business was suspended, schools were closed and agitated

Patriots and Tories gathered in the streets. As news of the Continental Army's

plight filtered in, roads leading from the city were crowded with refugees all

fleeing the city.

In the Pennsylvania Statehouse Yard a

town meeting was called and newly arrived General Thomas Mifflin addressed the

crowd and much of Continental Congress. After listening to his appeals for unity

and support, Congress formally appealed to the militia of Philadelphia and those

in nearest counties to join Washington's beleaguered Army. Congress also sent

word to all parts of the country for reinforcements and supplies, and then

ordered Mifflin to remain in Philadelphia for consultation and advice. Mifflin

organized and trained three regiments of militia of the city and adjoining

neighborhoods, sending a body of 1,500 men to Washington. The General also

orchestrated the complex re-supply of the Washington's

ragged American forces once they reached safety on the Pennsylvania

side of the Delaware River. These Mifflin measures were critical components

needed by Washington

to cross the Delaware into New Jersey and counterattack the "fatheaded"

British Army on Christmas Day in Trenton. After the successful win at Trenton,

General Mifflin, accompanied by a Committee of the legislature, made the tour of

the principal towns of Pennsylvania. Through his stirring oratory Mifflin

recruited many men into the ranks of the Continental Army. Washington's army

reassembled once again in Pennsylvania and crossed the Delaware taking the brunt

of the British regular forces head-on just outside of Trenton. That evening

Mifflin came up with more desperately needed reinforcements adding to

Washington's troops nighttime advance that outmaneuvered the British attacking a

weak flank in the college town of Princeton. This battle was won and the troops

moved safely north into the hills of Northern New Jersey.

In recognition of his services, Congress commissioned Mifflin as a major-general

on February 19th, 1777 and made him a member of the Board of War.

On the Board of War, General Mifflin

joined a growing number of delegates and generals who shared the dissatisfaction

at the "Fabian policy" of General Washington. The war was going poorly

by the summer of 1777 with Major General Arthur St.

Clair's loss of Fort Ticonderoga. Clearly, at the very least, Thomas Mifflin

sympathized with the views of General Horatio Gates and General Thomas Conway

who blamed Washington for the losses of the Continental Army. In the late fall

of 1777 Horatio Gates, with the help and field leadership of Benedict Arnold,

defeated General Burgoyne's forces at Saratoga. Almost immediately Washington's

enemies embolden with the victory and sought his replacement with the "Hero

of Saratoga," General Gates. Thomas Conway, with Mifflin doing nothing to

stop the political intrigue, organized an effort in the Board of War to

establish Gates as the new Commander-in-Chief. Mifflin vehemently declared,

after Washington overcame the now notorious Conway Cabal that he had not

participated in their efforts to remove General Washington as

Commander-in-Chief. The Conway Cabal and responsibilities of his various

offices so impaired General Mifflin's health that he offered his resignation.

Congress refused to accept it. However, General Mifflin was replaced by General

Nathanael Greene in the quartermaster's department in March, 1778, and in

October of 1778 he and General Gates were discharged from their places on the

Board of War.

More

trouble followed from Mifflin's "loosing side" affiliation after his

replacement on the Board of War. An investigation of his conduct was

ordered by Congress resulting from charges that the distresses of the army at

Valley Forge were due to the mismanagement of the Quartermaster-General. When

the decree was revoked, after he had himself demanded an examination, he

resigned his commission. Congress refused to accept it, and placed in his hands

$1,000,000 to settle outstanding claims.

In

January1780, Mifflin was appointed on a board to devise means for retrenching

expenses. In this capacity he once again became a stalwart and strong advocate

of General Washington during the darkest days of the revolution. After the

achievement of the Treaty of Paris Mifflin was elected as a delegate to

new United States in Congress Assembled that was formed after the

ratification of the Articles of Confederation on March 1, 1781. Thomas Mifflin

served tirelessly as a Delegate and was so respected by his fellow delegates for

his good work and conduct during the 1780-81 campaigns that he was elected

President of the United States in Congress Assembled, on November 3, 1783.

His

presidency lasted only six months, as Congress adjourned on June 3, 1784 until

it reconvened with a new President in November 1784. On his presidential

election the Journals of the United States in Congress Assembled report:

Pursuant to the Articles of

Confederation, the following delegates attended:

FROM THE STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, Mr. A[biel] Foster, MASSACHUSETTS,Mr. E[lbridge]

Gerry, who produced a certificate under the seal of the State, signed

John Avery, Mr. S[amuel] Osgood, RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE

PLANTATIONS, Mr. W[illiam] Ellery and Mr. D[avid] Howell, CONNECTICUT, Mr.

S[amuel]

Huntington and Mr. B[enjamin] Huntington, NEW YORK, Mr. James Duane, NEW JERSEY,

Mr. E[lias] Boudinot, MARYLAND, Mr. D[aniel] Carroll,Mr. J[ames] McHenry,

VIRGINIA.Mr. J[ohn] F[rancis], Mr. A[rthur] Lee, NORTH CAROLINA, Mr. [Benjamin]Hawkins,

and Mr. [Hugh] Williamson, SOUTH CAROLINA, Mr. J[acob] Read, Mr. R[ichard]

Beresford, Seven states being represented, they proceeded to the choice of a

President; and, the ballots being taken, the honorable Thomas Mifflin was

elected.

Mifflin's first mission, as the new

President, was to insure that the Treaty of Paris was ratified under the six

month time constraint set forth in the agreement. President Mifflin scheduled a

ratifying convention at the Maryland State House in Annapolis in November 1783,

but many of the delegates failed to arrive. By mid-December Mifflin's attempt to

assemble a ratifying quorum became desperate. On December 15th Congress even

failed to achieve even the simple seven state quorum to read foreign dispatches.

Once again, on December 17th Congress failed to convene the mandatory nine state

quorum to conduct ratification despite the news of George Washington's impending

audience to resign as Commander-in-Chief. According to Ramsay:

In every town and village, through

which the General passed, he was met by public and private demonstrations of

gratitude and joy. When he arrived at Annapolis, he informed Congress of his

intention to ask leave to resign the commission he had the honor to hold in

their service, and desired to know their pleasure in what manner it would be

most proper to be done. They resolved that it should be in a public audience.

George Washington's

attendance in Congress set the stage for one of the most remarkable events of

United States history under Thomas Mifflin's Presidency. In November of 1783 the

British finally evacuated New York and Congress made the momentous decision to

place the Continental Army on "Peace Footing". It was in Annapolis, where

the US Government convened, that the last great act of the Revolutionary War

occurred. George Washington was formally received by President Thomas Mifflin

and Congress. Instead of declaring himself King or dictator as many men feared

while others hoped, Washington resigned his commission as Commander-in-Chief to

the President of the United States. What made this action especially remarkable

was that George Washington, at his pinnacle of his power and popularity,

surrendered the commission to President Thomas Mifflin, who by all accounts,

conspired to replace Washington as Commander-in-Chief with Horatio Gates (see

the chapter on Henry Laurens for a full account) in 1777. The United

States in Congress Assembled Journal account of George Washington's December 23,

1783 resignation is as follows:

According to order, his Excellency

the Commander in Chief was admitted to a public audience, and being seated, and

silence ordered, the President, after a pause, informed him, that the United

States in Congress assembled, were prepared to receive his communications;

Whereupon, he arose and addressed Congress as follows:

'Mr. President:

The great events on which my

resignation depended, having at length taken place, I have now the honor of

offering my sincere congratulations to Congress, and of presenting myself before

them, to surrender into their hands the trust committed to me, and to claim the

indulgence of retiring from the service of my country.

Happy in the confirmation of our

independence and sovereignty, and pleased with the opportunity afforded the

United States, of becoming a respectable nation, I resign with satisfaction the

appointment I accepted with diffidence; a diffidence in my abilities to

accomplish so arduous a task; which however was superseded by a confidence in

the rectitude of our cause, the support of the supreme power of the Union, and

the patronage of Heaven.

The successful termination of the

war has verified the most sanguine expectations; and my gratitude for the

interposition of Providence, and the assistance I have received from my

countrymen, increases with every review of the momentous contest.

While I repeat my obligations to

the army in general, I should do injustice to my own feelings not to

acknowledge, in this place, the peculiar services and distinguished merits of

the gentlemen who have been attached to my person during the war. It was

impossible the choice of confidential officers to compose my family should have

been more fortunate. Permit me, sir, to recommend in particular, those who have

continued in the service to the present moment, as worthy of the favorable

notice and patronage of Congress.

I consider it an indispensable

duty to close this last act of my official life by commending the interests of

our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the

superintendence of them to his holy keeping. Having now finished the work

assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of action, and bidding an

affectionate farewell to this august body, under whose orders I have so long

acted, I here offer my commission, and take my leave of all the employments of

public life'”

George Washington then advanced and

delivered to President of the United States his commission, with a copy of his

address, and resumed his place. President Thomas Mifflin returned him the

following answer:

Sir,

The United States in Congress assembled receive with emotions, too affecting for

utterance, the solemn deposit resignation of the authorities under which you

have led their troops with safety and triumph success through a long a perilous

and a doubtful war. When called upon by your country to defend its invaded

rights, you accepted the sacred charge, before they it had formed alliances, and

whilst they were it was without funds or a government to support you. You have

conducted the great military contest with wisdom and fortitude, through

invariably regarding the fights of the civil government power through all

disasters and changes. You have, by the love and confidence of your

fellow-citizens, enabled them to display their martial genius, and transmit

their fame to posterity. You have persevered, till these United States, aided by

a magnanimous king and nation, have been enabled, under a just Providence, to

close the war in freedom, safety and independence; on which happy event we

sincerely join you in congratulations.

Having planted defended the standard of liberty in this new world: having taught

an useful lesson a lesson useful to those who inflict and to those who feel

oppression, you

retire from the great theatre of action, loaded with the blessings of your

fellow-citizens, but your fame the glory of your virtues will not terminate with

your official life the glory of your many virtues will military command, it will

continue to animate remotest posterity ages and this last act will not be

among the least conspicuous .

We feel with you our obligations

to the army in general; and will particularly charge ourselves with the

interests of those confidential officers, who have attended your person to this

interesting affecting moment.

We join you in commending the

interests of our dearest country to the protection of Almighty God, beseeching

him to dispose the hearts and minds of its citizens, to improve the opportunity

afforded them, of becoming a happy and respectable nation. And for you we

address to him our earnest prayers, that a life so beloved may be fostered with

all his care; that your days may be happy, as they have been illustrious; and

that he will finally give you that reward which this world cannot give.

On the following day, December the

24th, President Mifflin once again appealed to States to send their required

representatives. Not even the resignation of George Washington was enough

incentive to attract a quorum of delegates for the ratification of the

Definitive Treaty of Peace between the United States and Great Britain. In this

Christmas Eve letter Mifflin makes a passionate plea to New Jersey and

Connecticut::

I had the honor to write to your

Excellency on the 23rd November, informing you that the definitive Treaty was

arrived, and that the last article of it declares that it should be ratified &

exchanged within six months from its Signature.

Yesterday I again writ to your

Excellency by order of Congress informing you that only Seven States were

represented in Congress viz. Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania,

Delaware, Maryland, Virginia & North Carolina, and that the ratification of the

definitive Treaty & several other matters of the greatest consequence were

delayed by want of a representation of Nine States.

My Letter of yesterday was

forwarded by the post, but as Congress are strongly impressed with an

apprehension that the time mentioned in the definitive Treaty will elapse,

before a representation of nine States can be obtained, and as such a

representation cannot take place unless New Jersey and Connecticut send on their

delegates, they have instructed me to write to you by Express, and to urge in

the strongest terms the importance of an immediate representation in Congress

from the State of New-Jersey. Let me therefore entreat your Excellency to use

your influence on this

important point,

that the consequences to be expected from the Want of an immediate

representation of nine States may not be imputable to your State, which on every

former Occasion has exerted itself with so much honor and reputation.

New Hampshire has but one Member

attending, and there is no probability of a representation of that State in less

than Six Weeks. New York has no delegates in Congress, nor can it be represented

in many Weeks. South Carolina has one member attending; one of the delegates

from that State is in ill health at Philadelphia; his attendance uncertain.

By letters from Georgia we find there is no probability of a representation from

thence this Winter; from this view of our situation your Excellency will observe

that the Ratification of the definitive Treaty in proper time, depends upon the

immediate exertions of New Jersey & Connecticut.

I should be glad to know from your

Excellency by the return of this Express, at what time we may expect a

representation from your State.

Later that day the President wrote

Governor Livingston a personal letter:

I have already addressed three

several dispatches to your Excellency of the 23d of November & of the 23d & 24th

of December stating to you the arrival of the Definitive Treaty and the

necessity, by an Article thereof, of its ratification and Exchange at Paris by

the 3d of March next: I have also stated in those dispatches the particular

situation of Congress. Nine States being necessary to a Ratification & Seven

only being present. Apprehending that these Letters may have miscarried & having

Reason to believe that the Representation from South Carolina will be compleat

in a day or two, I have dispatched Col. Harmar my private Secretary with this

Letter to your Excellency, informing you that if the Delegation of New Jersey

attends in Congress without further delay we may yet ratify the Treaty in time.

A Representation of Nine States to ratify the Definitive Treaty before the Time

limited for its Exchange expires must appear to your Excellency too important to

be longer delayed.

More on

Thomas Mifflin - Click Here

Click Here

In this powerful, historic work, Stan Klos unfolds the complex 15-year

U.S. Founding period revealing, for the first time, four distinctly

different United American Republics. This is history on a splendid scale --

a book about the not quite unified American Colonies and States that would

eventually form a fourth republic, with

only 11 states, the United States of America: We The People.